- Home

- Ibtisam Azem

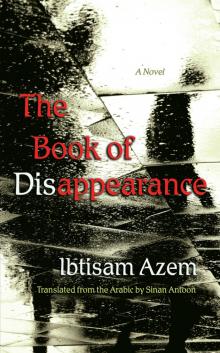

The Book of Disappearance

The Book of Disappearance Read online

Select Titles in Middle East Literature in Translation

The Candidate: A Novel

Zareh Vorpouni; Jennifer Manoukian and Ishkhan Jinbashian, trans.

A Cloudy Day on the Western Shore

Mohamed Mansi Qandil; Barbara Romaine, trans.

The Elusive Fox

Muhammad Zafzaf; Mbarek Sryfi and Roger Allen, trans.

Felâtun Bey and Râkim Efendi: An Ottoman Novel

Ahmet Midhat Efendi; Melih Levi and Monica M. Ringer, trans.

Gilgamesh’s Snake and Other Poems

Ghareeb Iskander; John Glenday and Ghareeb Iskander, trans.

Jerusalem Stands Alone

Mahmoud Shukair; Nicole Fares, trans.

The Perception of Meaning

Hisham Bustani; Thoraya El-Rayyes, trans.

32

Sahar Mandour; Nicole Fares, trans.

For a full list of titles in this series, visit https://press.syr.edu/supressbook-series/middle-east-literature-in-translation/.

Copyright © 2019 by Sinan Antoon

Syracuse University Press

Syracuse, New York 13244-5290

All Rights Reserved

First Edition 2019

19 20 21 22 23 24 6 5 4 3 2 1

Originally published in Arabic as Sifr al-Ikhtifa’ (Beirut: Dar al-Jamal, 2014).

∞ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

For a listing of books published and distributed by Syracuse University Press, visit https://press.syr.edu.

ISBN: 978-0-8156-1111-0 (paperback)

978-0-8156-5483-4 (e-book)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: ‘Āzim, Ibtisām, 1974– author. | Antoon, Sinan, 1967– translator.

Title: The book of disappearance : a novel / Ibtisam Azem ; translated from the Arabic by Sinan Antoon.

Other titles: Sifr al-ikhtifa’. English

Description: First edition. | Syracuse, New York : Syracuse University Press, 2019. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2019016085 (print) | LCCN 2019017760 (ebook) | ISBN 9780815654834 (E-book) | ISBN 9780815611110 (pbk.)

Classification: LCC PJ7914.Z35 (ebook) | LCC PJ7914.Z35 S54 2019 (print) | DDC 892.7/37—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019016085

Manufactured in the United States of America

For Tata Rasmiyye.

For Sidu Mhammad, Ikhlas, Abla, and Salim.

For Jaffans.

Contents

1. Alaa

2. Alaa

3. Alaa

4. Ariel

5. Flower Farm

6. Bus Stop

7. Prison 48

8. Hospital

9. A Building

10. Ariel

11. Ariel

12. Ariel

13. Sahtayn Hummus

14. Airport

15. Ariel

16. Alaa

17. Alaa

18. Ariel

19. Ariel

20. Alaa

21. Alaa

22. Alaa

23. Ariel

24. Rothschild Boulevard

25. Chez George

26. Ariel

27. Ariel

28. Rothschild Boulevard

29. Chez George's

30. A Man and a Memory

31. Ariel

32. Ariel

33. Alaa

34. Alaa

35. Ariel

36. Ariel

37. At the Gates of Umm al-Gharib

38. Ariel

39. Ariel

40. Ariel

41. Ariel

42. Ariel

43. Rothschild Boulevard

44. Ariel

45. Ariel

46. Alaa

47. Ariel

48. Alaa

49. Ariel

Afterword

1

Alaa

My mother put on mismatched shoes and ran out of the house. Her curly hair was tied back with a black band. The edge of her white shirt hung over her gray skirt. Fear inhabited her face, making her blue eyes seem bigger. She looked like a mad woman as she roamed the streets of Ajami, searching for my grandmother. Rushing, as if trying to catch up with herself. I followed her out. When she heard my footsteps, she looked back and gestured with her broomstick-thin arm: go back!

“Stay home, maybe she’ll come back.”

“But Baba is there.”

“Then go to her house, and then to al-Sa‘a Square. Look for her there.”

She went frantically from house to house. So tense, she looked like a lost ant. Knocking on doors so hard I was afraid she’d break her hand. As if her fist was not flesh and bones, but more like a hammer. She didn’t greet whoever came out and just asked right away if they’d seen my grandmother. If no one answered, she’d take a deep breath and weep before the closed door. Then she’d go on to the next house, wiping her tears away with her sleeves.

I followed her, like a child. I’d forgotten how fast her pace was. I was forty and had retained only faint and distant memories from that childhood. I was afraid she’d get hurt. I’d never seen her so overtaken by fear. She looked back every now and then, perplexed that I insisted on following her. I stayed a few steps behind. I felt too weak to challenge this woman: my mother. I begged her to go home and told her I’d search Ajami, house by house, to find Tata. She gestured again with her arm, as if I were a mere fly blocking her way. She kept searching and the houses spat her out, one by one.

I had gone home to our house in Ajami about an hour earlier to catch the sunset in Jaffa. I go twice a week, usually two hours before sunset, and wait until we are all sleepy before heading back to my apartment in Tel Aviv. Tata had moved to live with my parents six months earlier. Mother insisted that she move in after having found her unconscious in her bathroom, her leg almost broken.

Tata’s house on al-Count Street was just a ten-minute walk away. “Al-Count” is the old name Tata still insisted on using. I had put “Sha‘are Namanor” on the mailbox. What am I saying? She didn’t “insist” on using that name. That was its name. Al-Count sounded strange to me when I was a child. But later Tata told me that it was the honorific given by the Vatican to Talmas, the Palestinian man who donated money to build the Maronite church in Jaffa. He had lived on this street and it took his name.

After she moved to live with my parents, Tata insisted on going back every morning to water her roses and tend to them. Mother would accompany her and she or my father would later go back, just before sunset, to bring Tata back home. That morning Tata said she felt a bit tired and didn’t go to her house. She went out alone, which was unusual, an hour after mother did. That’s what my father said when I got home. When my mother came back after visiting a friend and buying a few things she was terrified.

The day squandered its minutes before my eyes. I was tired of following my mother, so I left her and hurried to al-Sa‘a Square. Tata loved it. We called her Tata, not sitti. She didn’t like sitti.

But then I came back. She won’t be there. There was no place to sit and look at Jaffa there. I figured that she must’ve gone to the shore, the one near the old city. She loved that spot. So I hurried toward the sea, to the hill where she liked to sit. To get there quickly, I had to go through the artists’ alleyways in the old city. I hated walking through them.

Will I find her? Will I find Tata? I felt my heart choking.

I heard my breath stumbling as I went through the narrow alleyways between the dollhouses. That’s

what I used to call the artists’ galleries there. I felt a sudden pain in my chest as I ran up the old steps. As if my lungs had become narrow, just like those alleyways. When I used to pass through old streets as a child I would see my shadow walking next to other shadows. Sometimes it would leave me, as if it had become someone else’s shadow. I thought I was crazy and kept this a secret for years. Once I was with Tata and I asked her to take another route that doesn’t go through the old city. She laughed, kissed my head, and held my hand. “Don’t be scared, habibi. All the Jaffans who stayed here see a shadow walking next to them when they walk through the old city. Even the Jews say they hear voices at night, but when they go out to see who it is, they don’t find anyone.”

Her story didn’t help me knock out my fear. It overwhelmed me and still haunted me even as I got older. I reached the open square overlooking the sea. The sea surprises me every time I come here after escaping the jaws of the old city’s alleyways. I felt a dry wind touching my lips as though in a desert. The sea is before me, yet I feel I am in a desert. I looked north, beyond Jaffa. The glass windows of the other city, the white city, the city of glass, shot their reflections back at me.

I headed to the hill next to Mar Butrus Church. I felt the church, too, was tired.

I found her.

She was sitting on the wooden bench, looking at the sea. I called out loud, happiness lilting in my voice as I ran toward her: “Tata! Tata! Tata!” I looked at her tan face gazing at the sea. A strand of black hair had managed to slip away from her headscarf, as if to dance with the wind. A light smile perched on her lips. I sat next to her and held her hand. “You scared us to death!” Her fingers were wooden, dry even though her body did not feel cold, to me at least. When I shook her shoulder, she leaned a bit. I held on to her shoulder again with my shaking fingers. Had she fainted? I placed my ear on her chest to see if she was breathing. I felt suffocated, as if all of Jaffa was caged in my chest. I took out my cell phone to call for an ambulance. I could barely force words out of my dry mouth. All that water around me, yet my mouth was still so dry.

She was sitting on the old wooden bench gazing at the sea. Surrounded by the noise of the children playing nearby. “Children are the birds of paradise,” she used to say. Mother would shoot back, “God save us from such birds. They’re all noise and no fun. Oh God, will there be noise in paradise too?” None of the passersby noticed that she had died. She died just the way she’d wanted: either in her bed, or by the sea. She used to pray that she’d never get so old to need anyone’s help. “Please, God, don’t let me be dependent on anyone. Take me to you while I am still strong and healthy.” I inched closer and hugged her. Perhaps she was the one hugging me at that moment. I knew it would be our last moment alone, before the ambulance came. I could smell jasmine, her favorite scent. She surrounded herself with tiny bottles of it, everywhere in her house. I didn’t shed any tears. Perhaps I had yet to comprehend what had happened. Or maybe I didn’t want to believe that she had died. The only meaning that word had at that moment was a strange and overwhelming sense of emptiness. I called my father. He said mother was back at home and on the verge of madness. They were going to follow me to the hospital.

She took a bath before going out. As if going to her own funeral.

2

Alaa

“I lived my life, lonely,” she used to say. Even though her house was always full of guests, as I remember. But memory is dense fog that spreads or clears as one gets older. I never understood why she spoke of herself in the past tense so often. Even when she laughed, and she loved to laugh, she would still speak of herself in the past tense and would say, “I used to love laughing. Oh, how I loved laughing!”

Tata died.

I still get goose bumps whenever I say it. Tata died. I was relieved that she died without needing anyone. But she died.

She died.

She took a bath before leaving the house.

As if going to her own funeral!

She was sitting in the middle of the wooden bench, facing the sea. She was wearing her purple plissé skirt, and a matching shirt under her black chiffon coat. Without her tiny black purse this time. Or maybe someone stole it from her? How did she get here? A see-through black scarf hid her hair. She never let it go white and would always dye it black. Even after reaching her seventies, she would still paint her nails, making sure the colors matched her attire. “No one loves life the way we, the people al-Manshiyye, and of the sea, do.” She would always mock those who didn’t groom themselves, as if only city folk and Jaffans knew how to do so.

She liked to sit by the sea, often on the Arab beach, near Ajami. But she loved that other spot atop the hill where I found her, too, especially the wooden bench. I never knew why. And she died here, by the sea. She preferred to die in Jaffa rather than leave. Whenever she mentioned Jaffa’s name, she would take a deep breath, as if the city had, all of a sudden, betrayed her and scorched her heart. At that moment, when I saw that her body was a corpse gazing at the sea, I realized that there were so many questions I had yet to ask her. But death and time beat me to them. “How many times can one say the same thing? I swear sometimes I get sick of myself,” she used to say with a smile, when I asked her to retell one of her stories.

Longing for her is like holding a rose of thorns!

I noticed that she was clutching something in her right fist. When I tried to loosen her hand, I saw her pearl necklace. It had come loose in the past, but she didn’t want to have it restrung. Sometimes she used to take it out of its old wooden box, where it was wrapped in cotton, just to look at it. I asked my mother about it, but she didn’t know anything, or if the pearls were real or fake. I had a feeling she wasn’t telling the truth.

Tata had a black beauty mark on her right cheek, like the bezel of a precious ring. When I was a child I used to reach up to touch and kiss it. Mother has one, too, on her left cheek. When I looked at Tata’s face there was a light smile still alive, showing some of her teeth. “I don’t wear dentures,” she used to say, “No one believes that I am over eighty and don’t need them. My feet ache because of the sewing machine, but my teeth are like pearls.”

Why did Tata choose to die alone, facing the sea? Was she always lonely, even when she was with us? Something about survivors leaves them always lonely.

“I walk in the city, but it doesn’t recognize me,” she once said in a sad voice.

“Why would the city recognize you, Tata? It’s not like you’re Alexander the Great. You know the city is inanimate! It’s not a person.”

“What are you saying? Who told you a city cannot recognize its people? You kids don’t understand anything. A city dies if it doesn’t recognize its people. The sea is the only thing that hasn’t changed. But frankly, it’s meaningless. Lots of water for nothing.”

I laughed when she said that. She would take back her insult to the sea, as if it were the only thing that remained loyal. It neither changed, nor left. She would always complain that the streets were empty. They had many people, but were still empty. “All those people left their own countries and came here. What for? They crowd everything, but have no gravitas. I don’t like to walk down the street in the morning and not come across someone I know. There are only a handful of us left who can greet each other. Come, let’s stop by the pharmacy to say hello to Abu Yusif.”

I used to accompany her to al-Kamal Pharmacy. As soon as we enter, she would start complaining to Abu Yusif about the pain in her knees. I would remind her that he’s not a physician, but he would tell me to let her ask her question. Whenever she met one of those who stayed in Jaffa, she used to regress to a little girl. They would speak of “that year” and what happened before and after “that year.” When I was a teenager I used to mock the pharmacy’s name and its greenish wood. But now I’ve learned to love it. I get all my prescriptions there. I see Tata standing or sitting there, taking her time, and talking to the pharmacist. Always about Jaffans, their names, and news. I u

sed to get tired of all those names when I was young.

“He told me that we must leave. I’ve arranged everything and we must go to Beirut before they kill us all. We’ll come back when things calm down. I told him that am not leaving. I’m six months pregnant. What would we do if something happened on the way there? How could one leave Jaffa anyway? What would I do in Beirut? There is nothing there. I don’t like Beirut. You live in Jaffa, and think of going to Beirut? I never liked Beirut. I don’t know why people like it so much. Nothing worth seeing.”

Whenever sidu’s name came up, she used to repeat her answer to him, but would revise details here and there. Sometimes Beirut becomes beautiful, but it wasn’t her city and she didn’t want to go there. At other times Beirut was just a trivial hell.

“Weren’t you afraid?”

“Who said I wasn’t? A week before your sidu and my folks left, I thought I was going to have a miscarriage. The bullets were everywhere. They used to shoot at us whenever we went outside our houses. We were like mice. Our lives had no value. Why do you think everyone left the city? Do you know why my brother Rubin, my sister Sumayya, and all my uncles left? No one leaves just like that. That’s enough, grandson. Don’t hurt me even more.”

I waited two days and then asked her again about the house. She said it’s in al-Manshiyye. The building where her family lived was bombed and collapsed on top of those living in it. She was lucky that she felt severe pain that night, and her family was visiting her, so they slept over. When they went back the next morning, they didn’t find their neighbors. They all perished in the rubble of the building. The building died, and they died with it. It was a coincidence that her family survived. My grandfather and her family decided to go to Beirut until things calm down. But she refused to go with them. He was convinced that she would join him later. Her mother and siblings went with him. Her father, my great grandfather, stayed with her after she refused to go. He had hoped that he would join the others, or that they would eventually return. But they weren’t able to do so, and she didn’t want to leave. She inherited stubbornness from her father. My grandfather waited ten years for her, but she never joined him. She would always say, “I never left. He’s the one who left. I stayed in my home.”

The Book of Disappearance

The Book of Disappearance